Northwest Detention Center (NWDC) could easily be confused for a factory. Sitting in an industrial park on the shores of Tacoma, Washington, NWDC is a gray, rectangular building surrounded by wire mesh. Trucks come in and out all day long. Rather than dealing in material commodities, however, NWDC processes human beings.

Founded in 2004, the detention center holds immigrants indefinitely while the slow gears of the U.S. immigration machine push them towards deportation. NWDC is, in theory, not a prison, but rather a processing center for civil immigration violations. In practice, the Tacoma detention center is indeed a punitive institution, characterized by its reliance on solitary confinement and its deplorable living conditions. Despite not being a factory, the detention center is still a profitable endeavor, scoring political points for politicians peddling xenophobic policies and securing economic gain for GEO Group, the private prison corporation that controls the prison.

Nonetheless, the resistance of those being processed consistently obstructs the detention center’s mission. For the last ten years, NWDC has been a crucial political battleground between a dehumanizing immigration apparatus and the migrants detained inside, consistently refusing to be commodified. In 2014, 750 detainees kickstarted a hunger strike to demand their freedom. The strike formally stopped fifty-six days later, but it is still ongoing: Detainees organized hunger strikes in 2017 against Trump’s nativist policies. They did so again in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, using their bodies to spell the letters “SOS” when seen from the sky. In 2023, NWDC detainees organized seven hunger strikes. These strikes are supported by La Resistencia, an anti-detention organization led by immigrants, many of whom have loved ones detained or who have themselves spent time in the belly of the beast.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and GEO Group have responded to protests inside NWDC with blatant repression. In 2023, GEO Group set off tear gas inside Unit F4 and sent armed guards into the common area to restrain a hunger striker. In August 2023, the University of Washington’s Center for Human Rights showed that between 2016 and 2023, NWDC authorities used tear gas at least 29 times. These authorities have also placed incarcerated organizers in solitary confinement, threatened hunger strikers with force-feeding, and even refused state-mandated health and safety supervisions.

Unlikely as it may seem, the insider resistance of NWDC detainees is part and parcel of a political tradition that is deeply intertwined with the growth of immigrant detention itself. For historian Kristina Shull, immigrant protest has taken place inside detention centers from their inception. Furthermore, their violent repression is not an incidental element of the detention system. According to Shull, detention itself is a structural form of political repression—a form of counterinsurgency.

Reagan’s Empire of Cages: Immigrant Detention as Domestic Counterinsurgency

Shull’s Detention Empire: Regan's War on Immigrants & Seeds of Resistance provides a key to understanding contemporary reliance on detention centers, exploring a variety of official archives and unofficial counter-archives to show how immigrants exercise political agency within these institutions. Where much research situates immigrant detention as a parasitic outgrowth of U.S. mass incarceration, Shull adds a necessary layer of historical context by exploring the connections between U.S. counterinsurgency strategies in the broader American continent and the punitive treatment of displaced people arriving into the country. It is no surprise that the central historical turning point in Shull’s story is Ronald Regan’s presidency.

Shull argues that the roots of detention lay in a political crisis fabricated by the “Reagan imaginary”—a “vision and strategy of white nationalist-state making” that is “shaped by neo-conservative politics, neoliberal economics, and long-standing mythologies of settler colonialism.” In the early 1980s, the Reagan imaginary confronted various crises of continental displacement. Cubans, Haitians, and Central American migrants arrived at the U.S. around the same time by sea and land. The Reagan imaginary imputed onto these groups political and racial fears around communist infiltration, urban criminal violence, drug trafficking, and even unfettered sexuality. Immigrant detention functioned to control these politically manufactured panics; first in military bases turned into ad hoc refugee camps and eventually, detention centers based on a carceral model that brought about the virtual merging of immigration and criminal policy that marks our present epoch.

The first part of Detention Empire explains how government reception of each migrant group built up Reagan’s detention empire. Chapter 2 focuses on the arrival of so-called “Mariel Cubans” starting in the early 1980s; unlike prior post-revolution Cuban arrivals, they were far more likely to be Black and working-class. Chapter 3 traces the exclusion of Haitians via Ronald Reagan’s expansion of U.S. immigration power beyond borders through sea interdiction. Chapter 4 connects U.S. histories of Mexican detention with its Latin American empire-making through the detention of Central American would-be refugees on the U.S. Southern Border.

With the contextual groundwork laid, Shull spends the second portion of the text chronicling resistance of each of these migrant groups and their allies, including the Sanctuary Movement and the collaboration between Haitian asylum seekers and their allies on the outside. Chapter 6 closes the book by zeroing in on construction of immigrant detention centers in their contemporary form, through government and private action.

The Bipartisan War on Migrants and the Carceral Palimpsest

Detention Empire’s brightest moments come from Shull’s empathetic telling of everyday life, community, and resistance. In Chapter 2, Shull takes us inside the Fort Chaffee barracks, where Cuban migrants built vibrant and even contradictory counterspheres, including spaces of free expression for gender nonconformity and groups of activist “abuelas” that held pro-U.S. rallies to prove their patriotism from inside detention. Zeroing in on Krome Detention Center, in Florida, Shull describes dorm-room prayer services and even a “home-fashioned beauty salon” established by Haitian women behind bars.

While Shull’s main contribution lays in her telling of subaltern history, it is also worth underscoring the connections she makes between Reagan’s “detention empire” and the development of mainstream American politics in the 20th century. The Fort Chaffee saga demonstrates the centrality of detention measures in shaping immigration policies and politics to come. In the early 1980s, the military base was turned into a refugee camp to house Cuban arrivals. Slow processing and deplorable camp conditions nonetheless prompted a series of prisoner uprisings, reaching their zenith on June 1, 1980, when 1,000 Cuban migrants set fire to five buildings. These uprisings were swiftly repressed when then-Governor Bill Clinton called the National Guard into Fort Chaffee, though the refugee camp represented a political thorn in his side that was decisive in his electoral defeat that very year.

Clinton learned a valuable lesson on the power of immigrant scapegoating, making a comeback two years later to the Arkansas state executive in part by chastising his opponent, Governor Frank White, for failing to close Fort Chaffee—not as an act of mercy to migrants, but as a way of ridding Arkansan soil of a majority-Black population framed as invaders in mainstream discourse. Once he became president, Clinton would then spearhead a series of bipartisan policies to further criminalize migrants and in turn, drastically expand migrant detention.

The basis for this later expansion, Shull demonstrates, was laid out by Reagan administration figures like then-Associate Attorney General Rudy Giuliani, key jurisprudential architect of the Haitian interdiction and Cuban mandatory detention policies. In Congress, racist stalwarts like Senator Jesse Helms provided support for the expansion of U.S. counterinsurgency measures in Central America and for policies that treated Central American migrants as foreign threats, by warning that, “If Central America falls, we are going to be flooded with refugees.” Helms’s words exemplify the intrinsic connection that the Republican Party saw between counterinsurgency abroad and detention at home—a connection often overlooked by U.S. immigration scholars.

Shull’s key contribution to the emerging studies of the U.S. carceral state is her notion of the “carceral palimpsest.” A palimpsest is an arcane writing surface that is recycled repeatedly, with old writing giving way to new script without its traces being fully erased. In the carceral palimpsest, incarceration and detention practices contain traces of older structures. As the Reagan imaginary reacted to new immigrant groups, the administration deployed policies and criminalizing discourses already in place against non-white peoples.

In Chapter 6, for example, Shull describes the 1986 establishment of an immigrant detention center in Oakdale, Louisiana, a location chosen because of overwhelming local support for a penal economy, and isolation from outside advocacy organizations. Oakdale was “simultaneously pitched as a prison and not a prison and simultaneously humane and tough on crime.” The center initially housed Mexican migrants, but soon after its opening the federal government transferred Cubans to the facility.

In November 1987, Cuban prisoners inside took over the Oakdale prison, motivated by punitive conditions on the inside and by a Cuba-U.S. agreement to repatriate migrants on the outside. They set fire to the library, clashed with guards, and took 28 hostages. The prisoners eventually negotiated an agreement with the help of outside intermediaries, though as soon as the Cuban migrants ceded control of the facility, they were scattered across penal facilities in the country. Oakdale was remodeled and reopened in 1989 as a prison for “criminal aliens,” as part of the emerging intertwining of immigration and criminal law—new writing on an old palimpsest.

How Organizers, Academics, and Prisoners are Re-Writing the History of Detention

By the end of Detention Empire, it becomes apparent that many detention practices are debilitating and repressive by design. As seen in the Oakdale case, the INS learned that constantly transferring migrants across far-off facilities was a way of defusing political challenges. During the Oakdale stand-off, the government quelled dissent with Border Patrol Tactical Units, militarized forces created explicitly to put down prison uprisings. Immigration authorities also relied on public relations to condemn prison uprisings and even punished whistleblowers who spoke publicly about detention conditions. The repressive measures of the immigration regime extended outside prison walls, with federal charges and break-ins being used to intimidate the Sanctuary Movement for their work aiding Central American asylum-seekers. Together, Shull points out, these measures mirrored the counterinsurgency tactics being employed by U.S. operatives in Latin America at the same time.

Detention Empire ends where the tale of Northwest Detention Center begins. Faced with a massive population of detained migrants, the result of their own policies, the Reagan and Bush administration turned to their usual solution for governmentality crises: privatization. In 1983, Correction Corporations of America (CCA) signed the first-ever contract for a private immigration facility in Houston. Today, CCA and GEO Group maintain a duopoly on immigrant detention facilities, the latter operating NWDC.

Amid this story of incarceration, counterinsurgency, and deportation, Shull carries an abolitionist zeal borne from personal experience. In the introduction, she describes her ex-husband’s deportation as the moment that pushed her towards immigrant advocacy and scholarship. Shull has provided us with a text that embodies the very resistance it describes, using past episodes of unlikely resistance as guideposts for future organizing.

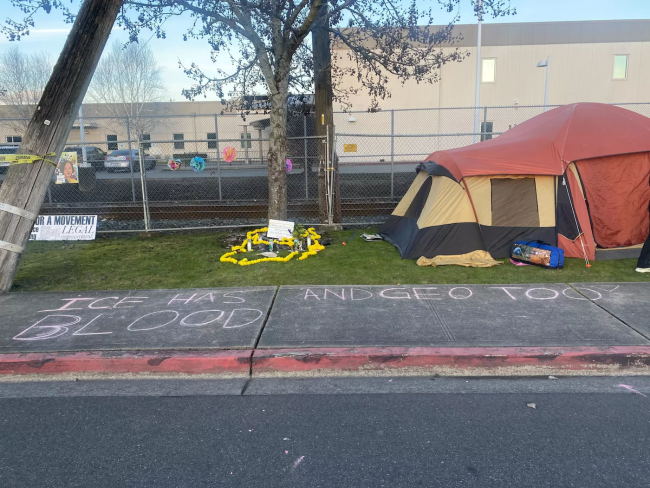

Onto the present, the Biden administration has continued the bipartisan reliance on immigrant detention, with all the profoundly repressive violence it entails. Like Shull, I have chosen to document this violence as an activist-scholar—namely, as a member of La Resistencia, in our struggle to close Washington’s NWDC. Earlier this month, on March 7, 2024, a 61-year-old Trinidadian detainee named Charles Leo Daniel was found dead at the prison’s solitary confinement wing, where he had spent nearly four years. In the past month, La Resistencia and Japanese American organization Tsuru for Solidarity set up an encampment in front of the prison to demand the permanent closing of the facility.

Posted next to a shrine dedicated to Charles Leo Daniel, the group’s founder, Maru Mora Villalpando, forewent all food for nearly two weeks. During the Trump administration, Villalpando was targeted for deportation by ICE for her activism on behalf of NWDC detainees, just as Sanctuary Movement organizers were targeted under Reagan for fighting on behalf of Central American migrants.

Inside the prison, 300 detainees organized another hunger strike less than 24 hours following Daniel’s death; as of this writing, at least 50 of them are still protesting, in defiance of old detention-counterinsurgency tactics. The carceral palimpsest, Shull demonstrates, is not only inked with chronicles of prisons and their brutality, but also with the resistance of those inside them. The detainees of NWDC, aided by organizers outside, are writing a new chapter that will one day close out the story of immigrant detention—a shameful, blood-stricken, transnational tale.

Ramón Garibaldo Valdéz is a Provost’s Postdoctorate Fellow in the Political Science Department of the University of Chicago. He is currently working on a book project tentatively titled, “La lucha de cada día: Immigrant Justice Organizing and the Political Remaking of Illegality in the U.S.”