Leer este artículo en español.

Liliana Cabrera arrived at the Ezeiza penitentiary complex in Greater Buenos Aires in 2006. At 26 years old, she had been convicted of crime against private property (i.e. theft) and sentenced to eight years in prison. A few weeks into her sentence, the older women in the prison organized a hunger strike. They demanded that inmates with children under five years old be granted the possibility of house arrest.

Immediately, Cabrera joined the strike. She saw plenty of inmates who, like her, didn’t have children but chose to fight for the other women’s rights. “In such a solitary context, I was shocked to find myself surrounded by women united for a common cause.” Their demand would later become part of the National Code of Criminal Procedure.

Through these other women, she learned about the feminist, anti-prison artistic collective Yo No Fui (“Yo no fui” translates to “It was not me”). At the time, Yo No Fui was a small group of women led by María Medrano, a poet who organized writing workshops at the Ezeiza prison. Cabrera recalls her friends telling her they had a good time during these meetings. They drank mate together and shared their thoughts. It was a space where they were called by their own names.

“I grabbed hold of writing because it helped me stay lucid in a context where lots of women just got depressed or relied on drugs to survive. I believe poetry saved me,” reflects Cabrera. After her release in 2014, she stayed on with Yo No Fui and now teaches the same workshop.

Medrano herself had always been a poet, but up until the early 2000s she worked in various administrative jobs in the national justice system. Several years before, in 1996, she witnessed a situation that would haunt her. A young Russian migrant in her twenties had arrived in Argentina without knowing any Spanish. Medrano saw this young woman convicted of prison for a minor felony related to drug trafficking. “I was shocked at how the system I was also part of treated her,” she recalls. Medrano saw “the lack of protection and support” the system afforded to this young woman, practically the same age as her at the time. “It helped me realize I wanted to be on the other side, defending people like her and not sending them to jail.”

Around this time, Medrano also published a poetry book called Unidad 3 (Unit 3). It gained popularity among the artistic community in Buenos Aires and, in 2002, she was invited by La Casa de la Poesía (a cultural center in the City of Buenos Aires that has been closed for renovation since 2012) to give workshops in unconventional spaces. So she chose the Ezeiza penitentiary, where she continued to visit and accompany the young Russian woman until she completed her sentence. They remain friends to this day.

Community Centered Approaches

Yo No Fui now operates in a total of three penitentiary units in Buenos Aires (two in Ezeiza and one in José León Suárez). There, they give poetry workshops to classes of 15 to 20 women at a time. Some inmates are regulars, while others come and go. Over the last 22 years, Yo No Fui has supported and accompanied hundreds of women and non-binary people. Medrano and the 30 or so individuals of Yo No Fui define themselves as a transfeminist and anti-prison collective.

“That’s the difference between us and nonprofits; we feel NGOs are part of a status quo, while we are trying to break with that political and social state of affairs,” the organization’s founder explains.

Formerly incarcerated women, local community activists, artists, therapists, academics, and more form a part of Yo No Fui. They believe the only solution to social problems comes from working together through a community-focused approach. That’s why the concept of collective is present in everything they do.

In March, they launched the Escuela, a school with workshops and classes focused on arts, office work, and transeminist politics primarily for the women and LGBTQ+ communities inside penitentiaries. The Escuela also seeks to involve local communities outside of the prisons, like those living in the Flores neighborhood, in the City of Buenos Aires, where the organization has facilities. The school is part of a multidisciplinary approach that seeks to give formerly incarcerated women the opportunity to reintegrate themselves and their families into society. Yo No Fui also developed a work cooperative that offers workshops and resources through which formerly incarcerated people can adopt practical and digital skills. The collective also has a self-managed publishing house called Tinta Revuelta. The members also accompany and support each other in care-focused initiatives, such as their espacio de segundeo (accompaniment space) which focuses on mental health.

The collective seeks to forge bonds between incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women and LGBTQ+ people, and local commuities. The strength from these communal bonds helps members rebuild their lives outside of prison.

Finding a Lifeline in Argentine Prisons

Over the last few years, the prison population in Argentina has grown exponentially. Between 2007 and 2020, the national incarceration rate grew by 55 percent, according to the Ministry of Justice. More than 45 percent of the people deprived of their liberty have not been convicted.

Of a total of 118,000 imprisoned people in the country, 49 percent are located in units and prisons under the responsibility of the Buenos Aires Penitentiary Service, according to the Comisión Provincial de la Memoria (Provincial Commission of Memory, CPM).

Overcrowding, lack of basic health services, and the systematic—and many times lethal—use of police force emerge as the main issues in Argentina's penitentiary complexes.

“Beyond the reasons that led me to prison, I can say I had a very solitary life; I didn’t share with others and I didn’t have a support system until I met this group,” Cabrera states, and adds: “If any of us has a problem, we know we have someone to talk to. This group’s a lifeline, an anchor.”

In penitentiaries in Argentina, people have the possibility of accessing therapists, but several members of Yo No Fui state that they felt a lack of trust. “Unfortunately, you know that everything you say will go to a criminological report and might be used against you, so at least for me, I didn’t feel completely comfortable sharing too much,” Cabrera explains.

According to a report by The Prison Ombudsman’s National Office, mental health programs in prisons are a central issue. Most therapeutic spaces are brief and unstable, and there’s widespread use of psychotropic drugs, mostly prescribed for people admitted with problematic drug use and for stress, anxiety, and difficulty sleeping. In the vast majority of cases, the report states, imprisoned people began using psychotropic drugs as soon as they were detained.

Members of the collective agree: that the system prioritizes medication over therapy. “If you’re a ‘nuisance’, the psychiatrist will prescribe some medication without psychological treatment just so you don’t bother [anyone],” Cabrera remarks.

The “Horizon” of Abolitionism

Yo No Fui runs on an abolitionist approach. As a result, members through the years have encountered people who ask questions like, “If we were to abolish prisons, what would happen with rapists and murderers?”

For Cabrera and her colleagues, there is no simple answer. “We acknowledge that we have put ourselves in a very uncomfortable position, but deep down we believe it’s necessary to have these hard conversations about a system that’s not doing anything to solve the problem.”

“The main challenge we face today is to think about ways to address all these issues other than building more prisons,” explains Claudia Cesaroni, lawyer and writer of several books, including Contra el Punitivismo (Against Punitivism in English). Alternatives include revisiting the cases of people who are imprisoned for small crimes related to personal drug consumption or retailing, and those imprisoned without having been proven to have committed a crime. Other possibilities include increasing the number of parolees, among others.

Abolitionism is both a practical organizing tool and a long-term goal. Some of its advocates include Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Black feminist and political activists from the United States. “We are not naïve; we see penal abolitionism as a horizon but also as a way to rethink all the intersecting systems and institutions that lead to the conception of prison as we know it today,” Medrano explains.

Through meetings with other Latin American organizations, including Red Feminista Anticarcelaria Latinoamericana, Yo No Fui searches for collective solutions to punitivism. “We’re still trying to learn from alternative justice and tools to mediate problems without jails and cops entering the scene,” Cabrera explains. She adds that when thinking about crime, one tends to only think about the transgressor and their actions, instead of questioning what other institutions and socioenvironmental factors perpetuate crime, such as sexual abuse.

This last statement has to do with a fundamental belief behind the abolitionist movement. By failing to question the social, historical, political, and economic conditions of the criminal system and its problems, the penal system ends up reproducing the oppressive social conditions it’s intended to address.

Addressing The Failure of Argentina’s Punitive Justice System

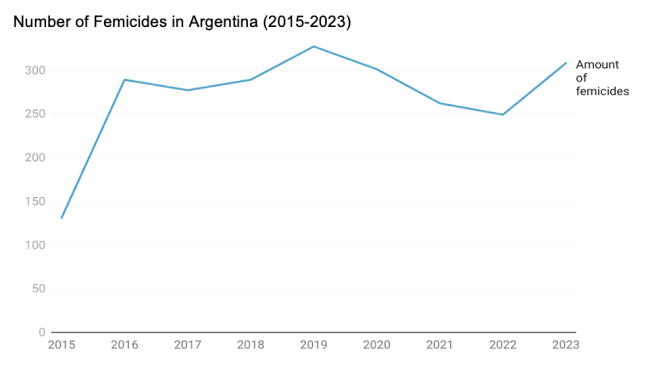

“One of the most evident signs of the failure of punitivism is that it always arrives late; after the crimes have already happened. To avoid their repetition, sanctions are increased or new penal figures are created, but it has been proven that this doesn’t fulfill its supposed preventive function in society,” Cesaroni explains. Cesaroni considers femicides in Argentina as an example. The crime of femicide was formally included in the Criminal Code in 2012, which is punished with life imprisonment. Gender-based crimes, however, have not significantly decreased.

Medrano also states that it’s important to question a penal system that always seems to “condemn and punish the same racialized, impoverished people.” She says, “We cannot fail to see [that] prisons have a color and a social class.” As said by Ruth Gilmore during a brief email exchange, abolition should not be seen as an “alternative to incarceration, unless what one has in mind is an alternative to the entire capitalist system.”

The myriad of problems of Argentina's prison system are reflected in its recidivism rates, or the number of people who complete their sentences and are imprisoned again.

A 2022 report by the Center for Latin American Studies on Insecurity and Violence shows that Argentina’s recidivism rate remained at 28 percent between 2002 and 2019. Argentina’s recidivism rate is lower than that of Southern Cone countries like Chile and Brazil, and higher than that of Central American countries as well as Mexico. However, it’s important to highlight that recidivism still represents an “exceptional phenomenon in women.” In 2019, eight percent of women imprisoned were classified as recidivists.

“Prisons today don’t work for what they were intended for. They don’t promote reflection in people or enable responsibility for their acts,” says Medrano. She adds, “In other words, you go to prison and you come out a mess.” What Medrano states is deeply related to the concept of the “right to hope,” repeatedly stressed by international organizations such as the European Court of Human Rights. Prisoners should have a realistic prospect of obtaining freedom. To deny the right to hope would be to deny a fundamental aspect of humanity.

Abolition fights for a world where prisons do not exist. However, Medrano is realistic about the present: “Some people out there tell us that what we do is a contradiction, like, ‘Why do you go to prisons to give workshops if you believe in abolition?’” In response, Medrano says, “Yeah, we are abolitionists. But since there are still many people in prisons, we will continue working there because, in the end, they are the reason why we’re doing all of this.”

Victoria Mortimer is a multimedia journalist from Buenos Aires covering culture and social politics in Latin America. She’s currently pursuing a Master’s in audience engagement and media product development at New York University.